OR: How You Bury Your Gays is Important.

There have been for queer people1 for pretty much as long as there have been people. Evidence exists of them in cave paintings: homosexual intercourse is shown in works made in 11,000 BCE2 by the San people of modern day Zimbabwe (Toomey, 2016) and wroks made by Upper Paleolithic Sicilians in the Grotta dell’Addaura caves near Palermo (queerstorian, 2017).

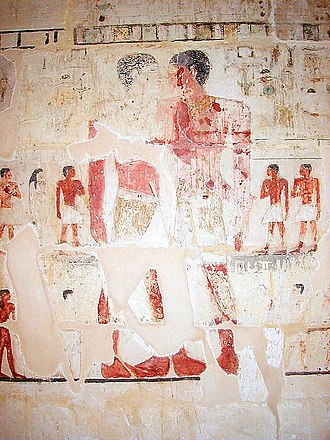

There’s also an abundance of evidence in burial sites. An Egyptian tomb from around 2500 BCE was discovered in 1964 and contained two men. While their given names are not known, the names on their tomb refer to them as Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum, which by some translations means “joined in life, joined in death”. The hieroglyphics from their tomb show that they were both chief manicurists of the palace, and that they both had wives and children, however those individuals are only shown in the background of pictures. The foreground is reserved for the men next to stand each other, often holding hands, nose to nose, or embracing. These poses would commonly show a married couple (Darling, 2025).

Photo courtesy of Moussa, Ahmed, Altenmüller, Hartwig.

Existing around the same time, the Corded Ware culture occupied most most Northern Europe, and held burial to be of high importance in their culture: males were buried on their right side, facing east and with weapons at their feet, and females were places on the left, facing west with an egg shaped stone at their feet. However many skeletons are found going against this norm. For instance the Prague 6 Archaeological excavation in 2011 contains many “traditionally” buried skeletons and one that has been analysed to be genetically and anatomically male, but was placed on their left and facing west, the way you’d expect from a XX and wide-hip-possessing female skeleton. The chief archeologist on this site, Kateřina Semrádová, stated that “We believe this is one of the earliest cases of what could be described as a “transexual” or “third gender” grave”. (Tann, 2011)

Additionally some graves do not conform to a cultural norm for either gender. Grave XV from the Stakeholm II site contains and a high status, spiritual leader from the Ertebølle culture who died between 5,400 BCE – 3,950 BCE, and led the archaeologist to suggest they had a “culturally unique identity” as “both the composition and the quantity of the grave accoutrements set this person very much apart from the rest of the group.” (Constandse-Westermann, 1998).

So queer people have always existed, but did queerness? Stanford archeologists Barbra Voss3 and Robert Scmidt aimed to answer this with their study of the Mesolithic period in Northern Europe, when farming and foraging started around 10,000BCE. They attempted to uncover how people felt about same-sex behaviour, the lived experience of people who practised this behaviour, and to what extent and how “[queer identities] could not be in containment or isolation from other aspects or qualities of [their] lives”. They concluded that sexuality was an important part of lived experience, as deep and complicated as it is in the 21st century. As the burial sites that go against the traditional gender norms of their time usually contain sharmans, healers, or spiritual leaders, showing some kind of social organisation bundled in with individual gender expression. (Voss, 2008) Further evidence comes from existing indigenous populations of Siberia and it suggests their gender non-conformity may have in fact been essential to their work: such peoples were believed to be able to manipulate biological-sex linked energy, allowing them to have unique insights into different planes of existence (Voss, 2000)

Of course so much of these findings are open to interpretation. Friend of the blog Barbra Voss described interpreting prehistoric evidence as like a Rorschach test where we place our own biases, both personal and of our culture, onto what we discover. With such a strong cultural focus on the ideal of a heteronormative nuclear family and a suspicion to anything that distorts that, it is no wonder that other conclusions have been made. When it was first discovered in the 1960s Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum’s tomb was thought to belong to brothers or twins as they are often shown in vaguely mirrored positions, despite the fact that siblings being buried together, or having a relationship regarded more highly than their romantic pursuits would be incredibly unusual for Ancient Egyptian culture (Darling, 2025). The “third gender grave” of Prague has been suggested to have been placed on the “wrong” side due to a neck injury, and the “wrong” objects being placed with them being a practical joke (Winter, 2015).

To me all of these things seem like a leap of logic, because of course they do: I live in a world full of gay people whose burials are sure to be super queer. Of course to me the most obvious answer is queerness. But that’s not the world other people live in, either out of the willful ignorance of homophobia and transphobia, or simply because they existed in a context where that kind of visibility couldn’t exist yet. While much of the evidence for queerness I will talk about going forward could also have other, straighter explanations, and sure there is an argument to be made that myself and other queer historians don't highlight thoes explanations out of a toxic, all consuming wokeness, it is important to remember those straighter explanations are also born out of values and beliefs.

Right that's most of the serious stuff done, it's Anceint Greeks and Romans next and they're much more fun.

Footnotes

1. To read more about how I’m using the term “queer”, what it means to me, and what it means within the scope of this project please my introduction to this project: https://queerswerehere.blogspot.com/2025/04/on-writing-queer-histories.html

2. I use BCE and CE rather than BC and AD not out of some anti-religious wokery, but because BC and AD is a system that uses both English and Latin, so I prefere BCE and CE that stays consistent to one language.

3. Barbra Voss is an absolute legend that I’ve become a bit obsessed with during this project. Read more about her on her website here: https://bvoss.people.stanford.edu/

Origionally posted April 2025, but keep having to change dates to keep posts in order.

References

Constandse-Westermann, T-S. 1988. Patterns of extraterritorial ornaments dispersion: An approach to the measurement of Mesolithic exogamy, p. 165.

Darling, H-H. 2025. Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum. https://www.makingqueerhistory.com/articles/2016/12/20/khnumhotep-and-niankhkhnum-and-occams-razor

queerstorian, 2017. Prehistoric Queer Art. https://worldqueerstory.wordpress.com/2017/06/02/cave-paintings/

Tann. 2011. Grave of stone age transsexual excavated in Prague. https://web.archive.org/web/20140204003857/http://archaeologynewsnetwork.blogspot.ca/2011/04/grave-of-stone-age-transsexual.html#.UvA2znbP32c

Toomey, P. 2016 Gay Sub-Saharan Rock Art In Zim. https://web.archive.org/web/20180705105326/http://www.jhblive.com/Stories-in-Johannesburg/article/gay-sub-saharan-rock-art-in-zim/82927

Voss, B. L. 2008. Sexuality Studies in Archaeology. https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev.anthro.37.081407.085238

Voss, B. L., & Schmidt, R. A. 2000. Archeologies of Sexuality. https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Archaeologies_of_Sexuality/ew-P2p4d-4MC?q=schmidt+2000+mesolithic&gbpv=0#f=false

Winter, J. 2015. The oldest gay in the Stone Age village-presumably! https://johnwinterblog.wordpress.com/2020/11/11/the-oldest-gay-in-the-stone-age-village/

Comments

Post a Comment